Adelaide to Cecily in 1990

Publié le 14/04/2011 par Michael de Montlaur — Famille

Dear Cecily,

My grandfather and grandmother on my mother’s side were brought up together and later married. Grandmother Piper was born in 1867 in Schoolies Mountains, New Jersey. She was called Marie Susan Cozzens. Her mother died when she was a little girl. Her aunt Adelaide Cozzens Piper had no children. She and her husband, Uncle Alec Piper, an army officer, brought her up.

Grandaddy Piper was born in 1865 at Fort Wadsworth, Staten Island, New York. He lost his father when he was ten and his mother soon after. He, too, went to live with Aunt Addy and Uncle Alec, his father’s brother. So he and “Dolly” as he called Grandmother, grew up together, almost like a sister and brother. Alexander Ross Piper went to West Point Military Academy as had his father and uncle. They had fought in the Civil War to defend the Union. They were from Pennsylvania near Lancaster, I believe. There is a small place called Piper’s Run where his great grandfather settled upon his arrival from county Armagh in Ireland toward the mid-18th century.

One of the Pipers, Uncle William, whose portrait hangs at the Farm in South Salem, New York, where we used to spend our summers when I was very young, had the reputation of being a great athlete. He was a member of the Pennsylvania state legislature. One day he made a bet with his colleagues that he could jump across the inside of the capitol dome in Harrisburg. According to legend he won his bet. It may be a tall story. At any rate, the family’s reputation for running and jumping remains to this day what with Uncle Alec Piper (my uncle) running the mile in competitions, your mother and her sisters and brothers who used to win all the ginger-bread prizes at the beach in Saint Jean de Luz and since then excelled in games like rugby, soccer and the like. And your uncle George arrived 2167th out of 24.000 in the New York marathon on November 4th, 1989. He even received a medal for perseverance!

After Grandaddy graduated from West Point in 1889 he was sent out West as a second lieutenant for frontier duty. He and Grandmother were married the next year and lived at Fort Robinson, Nebraska in the farthest western corner of the state, next to Wyoming. It was only a few years - maybe fifteen - since the unfortunate death, of Chief Crazy Horse at that very spot. Now there is a national park at Fort Robinson and an Indian reservation close by. But in the early 1890s the Sioux wars were still going on.

My grandmother was sometimes left alone. She kept a rifle near the door just in case there might be trouble. I wonder if she would have used it? She always drew the blinds before night fall. She didn’t want any Indians looking in those windows. She still did this even when she lived in New York many years later. Once I asked her, “Grandmother, don’t you want to see the end of the day?” But she felt very strongly on this point.

My mother was born in May 1891. Soon after her birth, her father was posted to Fort Omaha, still in Nebraska. The next year or so they moved south West to Arizona. They went first by train south through Kansas then to Texas and West through New Mexico and southern Arizona – it must have been the fairly recently built Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe line. They got off the train at a small station where they were met by a detachment of soldiers. The rest of the journey was overland by covered wagon to Fort Apache or Fort Bayard in the North of the state.

One day while he was stationed at Fort Bayard, some of his friends went with him on an expedition to hunt blue quail. He and the Captain’s son, 12 years old, went off in one direction. Climbing up a steep bank, my grandfather stumbled with a loaded gun. A shot went off. The bullet struck a rock and rebounded wounding him in the upper right arm. He told the boy how to tie a strip of cloth around his arm as a tourniquet to stop the flow of blood. Then the boy managed to help him onto his horse and they set out on a 50-mile trek to the nearest town where they could find a doctor. It was, alas, too late to save the arm. What pain it must have been then, and how many years he had to suffer, only he could tell us. The amputation was performed in a primitive way so far from civilization. And in the early 1890s medicine had not learned what we know now.

He remained in the army until 1899, after the Spanish American War when he served in Puerto Rico. He was awarded the Silver Star.

After retiring from the army he was active in New York City. As Deputy Commissioner of Police, he was sent to London in 1904 (or 1905) to study traffic methods. He attended the Lord Mayor’s banquet which takes place once a year when a new Lord Mayor takes office. At the same table he found Bill Cody, the famous Buffalo Bill of circus renown.

Now, if you remember the mounted police in New York, you will know they were there thanks to Captain Piper. Also the system of, one-way streets was introduced, as well as safety platforms at pedestrian crossings. He was known for strict discipline in the police force. A cartoon appeared in the newspaper of a policeman surprised at seeing Captain Piper emerging from a man-hole with the caption, “Where are your gloves?” He was very strict with his eldest daughter, Adelaide. No nonsense! She had to sit up very straight. It lasted all her life. They both could laugh and make jokes. But it is not a bad thing to exercise discipline!

One day much later, I was in the country visiting my grandparents in South Salem. An old country man named Cy Fowler came around to do odd jobs with his scythe. He had a hair-lip, a speech defect, but it didn’t seem to bother him. Grandaddy was supervising his work, walking along behind. Cy was mumbling and Grandaddy participated in the discussion from a distance. After Cy had gone home, I asked, “Grandaddy, what was Cy talking about?” – and he replied, “I don’t know. He don’t know either.”

My grandfather Piper and your grandfather, Guy de Montlaur, appreciated each other very much. They met in 1947 after World War II. Grandaddy still had five years to live after a long and interesting succession of careers and adventures. Your grandfather had just been through the war, beginning as a French cavalry man along the German frontier in the Saar. In 1940 he fought in a reconnaissance unit, racing through western France on a motorcycle with a side-car while the German armies overran the country. The armistice between France and Germany was signed in June 1940. He was forced to stop fighting near Limoges. He left France two years later for England after three months in Lisbon helping the British track down enemy agents who were dealing severe blows to British convoys at sea. He joined a Free French Marine unit attached to the British No 4 Commando. They trained in Wales, in the Scottish Highlands and along the South coast of England learning to live off the land, climb cliffs (such as the Seven Sisters), cross a river on a suspended wire, interminable quick marches, –“the training, he declared, was worse than the war.”

On D-Day, June 6, 1944, his landing barge was sunk amidst all the clamor. He and his section made a “wet landing” with their 100pound packs on their backs under heavy fire from the big guns of Merville on ‘the heights East of them beyond the canal and the river Orne. They ran across the beach at an even pace, not one of -the ten men was injured whereas anyone who lay down flat or fell was an easy target. Later in the morning their colonel was wounded. Resting along the way to their objective, the Casino at Riva Bella, Colonel Dawson shouted a word of encouragement, “Go to it, Guy” (Vas-y, Guy) Many years later he assured me he had never seen such a brave man as Guy de Montlaur.

The legend told in “The Longest Day” by Cornelius Ryan about the Count who lost a small fortune at the Casino before the war is still quoted on anniversaries of the landings such as the 40th on June 6, 1984 when Pierre Salinger told the story on TV news to the American public. When the Commandos were shown a “mute” map (a map ‘ showing no name places) before leaving England, your grandfather recognized the place. He knew Ouistreham with the Caen canal and the river Orne alongside. He had been to the casino with young friends during summer vacations. But he had never lost any sort of fortune there. It must heve been Commandant Kieffer who stretched the story to include a small fortune when Cornelius Ryan interviewed him for his book.

After holding the .Eastern end of the Normandy beach-head until mid-August, the Commandos with the rest of the British 6th Airborne Division .finally could advance across .the ·valley of the Dives, a valley well known to William the Conqueror. He assembled his fleet of “landing barges” at Dives before taking it up along the coast to St.-Valery-sur-Somme to invade England at Hastings across the Channel.

A little more than two months later, your grandfather again saw action, this time in the Netherlands, the Low Countries. Here there was a grave problem. .While the Germans kept a stronghold on the island of Walcheren at the mouth of the Scheldt, the Allies could not use the port of Antwerp. Belgium had been liberated more or less by the end of September. On the eve of All Saints Day which we call Halloween, October 31, 1944, the British and French Commandos crossed the ScheIdt, remaining quietly in their barges until early morning. It was a long dark vigil. In the landing barge at the back there was ammunition under the bench where three men were sitting. Bombardments began, the barge was sunk, blowing up the three unfortunate men in the back. The rest scrambled toward the huge anti-tank stakes driven in along the wharfs which they escalated, climbing up to the windmill called Oranje Mollen. Then began the siege of Flushing, the house-to-house fighting, bombing by their own air forces. After much loss of men where the dikes had been blown up at Westcapelle, and much trouble in that part of the island, Walcheren was finally liberated and the port of Antwerp ready for use.

Your grandfather did not return from the wars unscathed. Apart from his wounds, he carried the memory of everything he had seen with him until he died. He was a painter. He expressed the color of pain and suffering. He knew the shape, the size and proportion of what he had seen. One cannot talk about wars without dealing with unpleasant subjects. He could paint from the inside out. As he painted .non-objective or abstract or expressionist paintings, we need not know what he was expressing. Sometimes, though, we do need to know.

Dear, Cecily, this was meant to be an account of legends but it has turned out to be a history of facts. Please forgive me for not writing fairy stories or allegories. You may take what you like and leave what you don’t like.

My paternal grandfather Oates, born August 15, 1853 or 1854, in Weedon, Kent near London, studied to be a chemist. He went to Manchester, a textile center where the university had a science faculty especially directed to the needs of this industry. Did grandfather study there? I do not know. He married there and his father-in-law had certainly been active in the textile mills in his .time. It was the middle of the “industrial revolution” in England. Working conditions were very bad. In 1891 when Grandfather was promised a job in a chemical firm in New Jersey, he decided to leave England and took his wife and four children to America.

He wrote a journal on the boat, making such entries as to the weather each day, details about their cabins. One was uniquely reserved for all their belongings “everything but the kitchen sink”. They were invited to the Captain’s table. One day my father, then a little boy of three, climbed outside the rail on deck. What a fright! He nonetheless survived and lived to the great age of 99. His mother celebrated her 100th birthday on December 2, 1954.

After their arrival in New York my grandfather was told by the chemical firm they could not take him. Fortunately he had the idea of ~turning to the scientific publishers, D. Van Nostrand, in Gramercy Park, New York City and he stayed with them for at least forty years.

I remember vividly his beautiful white hair. The film, “Good bye Mr. Chips,” came to Great-Barrington in 1936. Everyone remarked how much Mr. Chips was the image of Grandfather. He looked like him and had the same voice. Mr. Robert Donat was extremely clever! Grandfather was very good at puns. ·He quietly altered Grandmother’s rather insistent suggestion, “Now, Harry, when you see the doctor, tell him you are much relieved” I heard him say under his breath “…muchly grieved !”

We were great friends and faithful correspondents in French (pidgin French on my part). In 1931 when we moved to California, he asked me to look very carefully to see whether Indians had beards. I wrote him back that no, they didn’t.

I said good bye to Grandfather Oates in the summer of 1936 just before I left with Aunt Cully and Aunt Bizzy and Aunt Marjorie who went with us to join Grandmamma and Grandpapa in England. Grandfather Oates died on November 15, 1936.

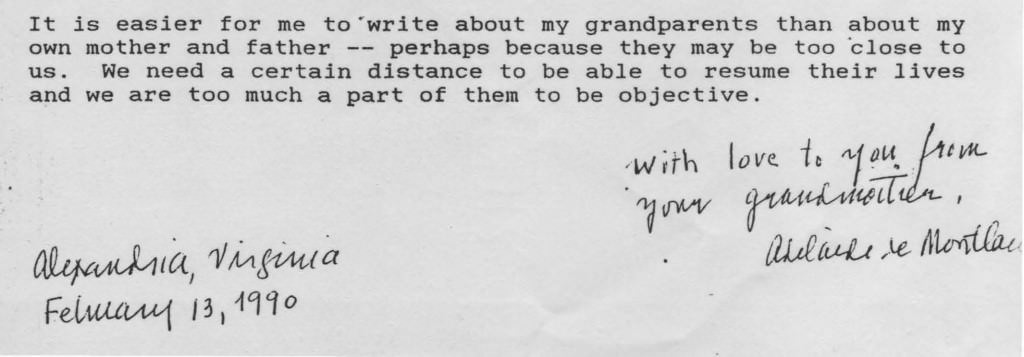

It is easier for me to write about my grandparents than about my own mother and father –perhaps because they may be too close to us. We need a certain distance to be able to resume their lives and we are too much a part of them to be objective.