Virtual exhibit

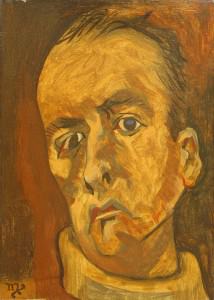

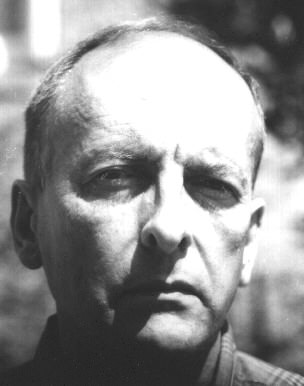

- Portrait

- 60-69

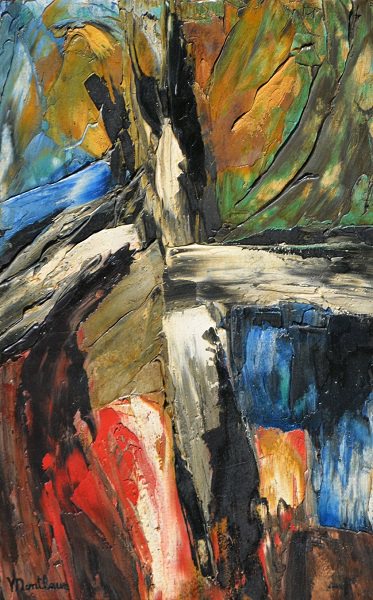

Composition abstraite

(Abstract Composition)

Montlaur is 49, he has reached the fullness of his art and of his technique. This small, slightly larger than life portrait, with an ironical title, is not meant to be flattering. The brown and ochre monochrome conveys an impression of sadness and weariness. His face is marked by the pain caused by his eye injury. The painter does not seek to please, he just paints. This is his whole life.

- Painting

- 70-77

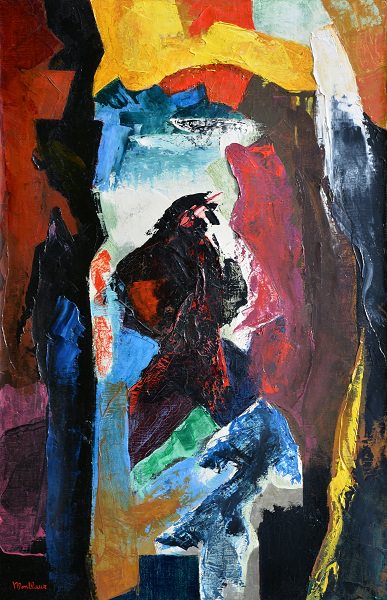

Souvenir d'Issenheim

Souvenir of Issenheim refers to the Issenheim Altarpiece painted by Matthias Grünwald and now visible at the Unterlinden Museum in Colmar. Montlaur’s painting reminds us of the innermost panel of the polyptich representing the torment of Saint Anthony by half-human, half-bird monsters sent by Satan. One can recognize the yellow and green colors of the monsters. The saint is lying on the ground with his blue robe. We can see the black veil behind him and the gray mountains at the top right. The chaos in both paintings is absolute.

Le Souvenir d’Issenheim is one of the last paintings by Guy de Montlaur.

- Religion

- 70-77

Quae est Ista

Quae est Ista quae ascendit

sicut aurora consurgens,

pulchra ut luna, electa ut sol,

terribilis ut castorum acies ordinata?

Who is This who ascends

like the rising dawn,

beautiful as the moon, bright as the sun,

terrible as an army drawn up in battle array?

(Song of songs, 6:9)

What more beautiful tribute, could the painter have paid to the Queen of the World, than this magnificent work, full of majesty, his very last, painted three months before his death?

- Painting

- 70-77

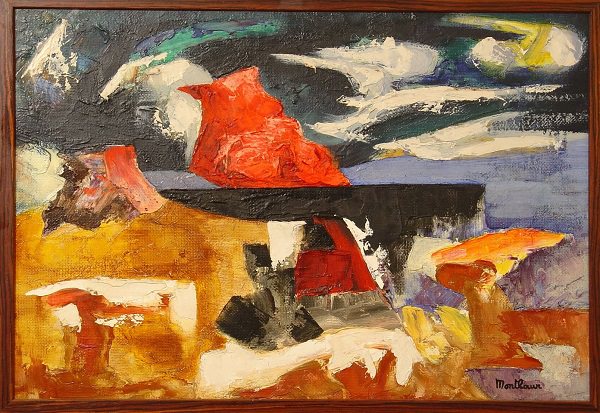

Peinture à l'usage des enfants

(Painting intended for Children)

The overall structure of the painting is geometric, it is composed and simple. Pastel colors are highlighted by deep black shapes. Here again, the superimposed layers of color appear when scraped. There is no violence, the painter is serene. He bequeaths his art, his technique to posterity, to children; it is as though he was telling them: “this is what I know how to do!”

- Philosophy - war

- 70-77

Le courage

(Courage)

Montlaur never lacked courage during the war years. From October 1939, he fought with the “Corps Francs” - commando-type units - and carried-out numerous raids in the Saar region, on the other side of the German border. In May-June 1940, he fought fiercely against the German troops that were storming through France, he fought well after the shameful armistice signed by Pétain and the Nazi regime. His courage is mentioned by Professor Guy Vourc’h in his tribute to his friend at his funeral in Normandy, on August 13, 1977: “I saw him when he arrived early 1943 (note: in London). I offered him the chance to join the Commandos which were the modern equivalent of cavalry, an arm used for reconnaissance and lightly armed bold raids. From that time onward, we were always together. First as group leaders, then as section leaders, training together with Commandant Kieffer, Lofi, Hattu, Chausse, Bégot, and Wallerand, we built up together an instrument of attack, which had the honor of being chosen as first to land, here, on our native soil of France. When all the officers of my company were wounded, it was Guy de Montlaur who took over in command. Later, at Flushing and Walcheren, wounded as he was near me, he refused to be evacuated. His courage was close to insolence; he was not just fighting but humiliating the enemy: by the age of 25 he had received seven citations for valor in battle and the French Légion d’Honneur.”

In February 1977, six months before the end of his life, Montlaur did not fear death which had been his intimate companion for so many years.

- Death

- 70-77

Le passeur des jours futurs - La mort d'une étoile

(The Ferryman of Future Days - Death of a Star)

Premonition of the painter’s death. The ferryman of future days is the guardian of the Styx: he is the focal point of this painting, dark red, color of blood, color of death. He is at the entrance of a world illuminated with pure white light. The painting was started in 1975 and completed in 1977, just a few months before Montlaur’s death.

- Religion

- 70-77

Quare conturbas me?

(Why are you creating disorder within me?)

Iudica me, Deus, et discerne causam meam de gente non sancta: ab homine iniquo et doloso erue me.

Quia tu es, Deus, fortitudo mea: quare me repulisti? et quare tristis incedo, dum affligit me inimicus?

Emitte lucem tuam et veritatem tuam: ipsa me deduxerunt, et adduxerunt in montem sanctum tuum, et in tabernacula tua.

Et introibo ad altare Dei, ad Deum qui laetificat iuventutem meam. Confitebor tibi in cithara, Deus, Deus meus.

Quare tristis es, anima mea? Et quare conturbas me? Spera in Deo, quoniam adhuc confitebor illi, salutare vultus mei, et Deus meus.

(Ps 43)

Judge me, O God, and plead my cause against an ungodly nation: O deliver me from the deceitful and unjust man.

For thou art the God of my strength: why dost thou cast me off? Why go I mourning because of the oppression of the enemy?

O send out thy light and thy truth: let them lead me; let them bring me unto thy holy hill, and to thy tabernacles.

Then will I go unto the altar of God, unto God my exceeding joy: yea, upon the harp will I praise thee, O God my God.

Why art thou cast down, O my soul? And why art thou disquieted within me? Hope in God: for I shall yet praise him, who is the health of my countenance, and my God.

(Psalm 43, King James version)

As in the psalm, the painting shows weariness and sadness, symbolized by the shape’s bent back and hanging arms. However, hope is present: a red and golden sun has taken the place of the heart.

- Philosphy

- 70-77

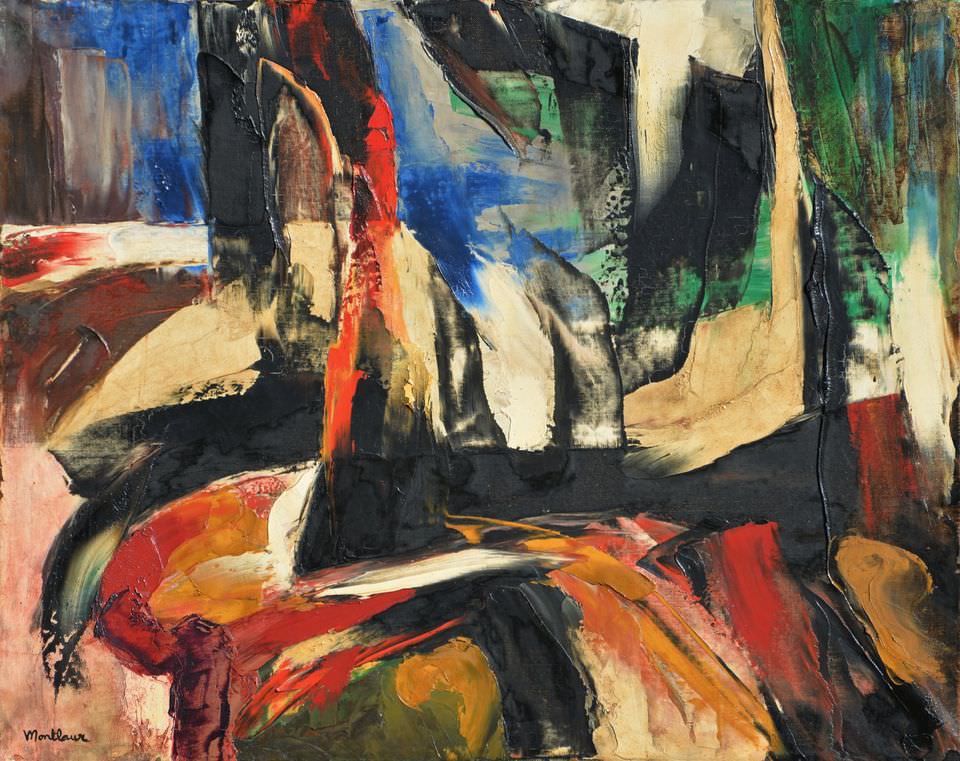

La connaissance des choses

(The Knowledge of Things)

This painting is a storm of colors, all vivid, never elementary: black is stained with yellow, green, blue, it is never sinister. The whites are slightly “dirty” (in the painter’s words). The reds are vermilion and carmine, blood-like. The patches of colors are almost always “scraped”, disclosing sometimes slightly, often frankly, the color of the underlying layer. In some places one can perceive the texture of the canvas.

A black figure stretching out both arms can be distinguished. Above it, there is a strange dark red sky and black, green, red, and yellow rectangular shapes.

The title, in English, is : “The knowledge of things”. What is painter referring to? Is this about knowing the things of the world, i.e. scientific and philosophical knowledge? Then, why the black silhouette? Nothing in the painting seems to confirm this interpretation. Did he mean: “I know my destiny”? The year is 1976: the artist died 18 months after completing this painting. He probably knows he has little time to live. He’s waiting for his old acquaintance, Death. He does not fear her. One last hypothesis, close to the one we have just considered: the soldier-artist with such a heavy past will undergo his last judgment. He is standing, his hands are extended towards the “Judge” who knows all things; he is confident.

- Classical literature - war

- 70-77

Arma virumque cano

Montlaur quotes the first verse of the Aeneid to explain the object of his painting: he sings about the hero’s feats of arms and his long journey after the war. One does not feel the horror of memory in this evocation, there is no blood, little black. The colors here are very unusual, they are clear and vivid and contrast with the green and blue fog of the landscape. At the focal point of the painting, we see a bright yellow, solar structure that could represent Lavium, founded by Aeneas the ancestor of the illustrious twins, founders of Rome.

Arma virumque cano, Troiae qui primus ab orisItaliam, fato profugus, Laviniaque venitlitora, multum ille et terris iactatus et altovi superum saevae memorem Iunonis ob iram;multa quoque et bello passus, dum conderet urbem,inferretque deos Latio, genus unde Latinum, Albanique patres, atque altae moenia Romae.

(Publii Vergili Maronis, Aeneidos liber primus, 1-7)

I sing of arms and the man, he who, exiled by fate, first came from the coast of Troy to Italy, and to Lavinian shores – hurled about endlessly by land and sea, by the will of the gods, by cruel Juno’s remorseless anger, long suffering also in war, until he founded a city and brought his gods to Latium: from that the Latin people came, the lords of Alba Longa, the walls of noble Rome.

(Virgil, Aeneid (Book 1.1-7)

(Translated by A. S. Kline, Poetry in Translation, 2002)

This painting is the property of The National WWII Museum, New Orleans, Louisiana.

- Poetry

- 70-77

Ma Désirade

(My Desired One) (La Désirade is also an Island off Guadeloupe)

Apollinaire’s beautiful poem about a past love.

The painting shows through a porthole the harbor, the coast of the island, or perhaps the beloved’s silhouette?

O Milky Way, whose sisterly

white streams flow on through Canaan’s land.

The white of lover’s bodies. We

must follow swimmers left unmanned

and swim to further nebulae.

The panther eyes I had to shun,

and beautiful but still a whore’s,

those Florentine, false kisses won,

in which the bitterness restores

distaste for what we might have done.

When looks across the evening brim

with stars that tremble in their haste,

and eyes in which the sirens swim,

and kisses blooded with such taste

to make the one who guards us grim.

In truth it is for her I’m sent,

and in my heart and soul’s recall,

and on that bridge where life’s re-sent

it may not have her sent at all

to tell her that I am content.

My heart and head are emptied wide,

all heaven’s flowing out of them,

and, heaped-up Danaïdes aside,

what happiness must I condemn

to be again a little child?

I’d not forget, though far I rove,

my dove upon the whitened road.

O marguerite in leaves unclothed,

my distant island, Désirade:

such rose you are and tree of clove.

(Guillaume Apollinaire, La Chanson du mal-aimé)

(Translated by C. John Holcombe)

- Poetry

- 70-77

Zénon ! Cruel Zénon ! Zénon d’Élée !

Zénon! Cruel Zénon! Zénon of Êlée!

You pierced me of this winged arrow

That vibrates, flies, and that does not fly!

The sound gives birth me and the arrow kills me!

Ah! the sun. . . Which shadow of tortoise

For the soul, motionless Achille to big step!

No, no! . . . Standing! In the successive era!

Break, my body, this pensive form!

Drink, my breast, the wind birth!

A freshness, exhaled sea,

returns Me my soul. . . O power salty!

Run to the wave some to reflect living.

(The Graveyard by the Sea, translated by Cecil Day Lewis)

- Poetry

- 70-77

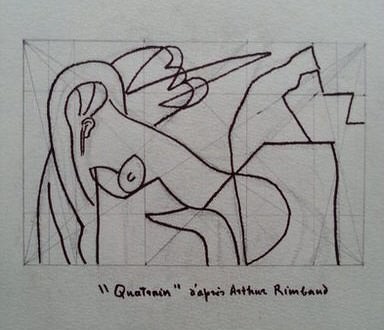

Quatrain

(Quatrain)

L’étoile a pleuré rose au cœur de tes oreilles,

L’infini roulé blanc de ta nuque à tes reins

La mer a perlé rousse à tes mammes vermeilles

Et l’homme saigné noir à ton flanc souverain

The star has wept rose-colour in the heart of your ears,

The infinite rolled white from your nape to the small of your back

The sea has broken russet at your vermilion nipples,

And Man bled black at your royal side.

(Quatrain, by Arthur Rimbaud, translated by Oliver Bernard)

Montlaur made a sketch of this painting (see above) which was quite unusual for him. This sketch is interesting and useful because it is more figurative than the painting and allows us to see the relationship between quatrain-painting and quatrain-poem. In the sketch, an ear is clearly seen, as well as breasts, nipples, and roll from the neck to the lower back. The man is hard to identify. In the quatrain-painting, the colors, so important for Rimbaud, are relatively well respected. The “Man bled black” appears unequivocally.

The artist is faithful to the poet: the painting and poem are an ode to the beauty of women or, more appropriately, of the goddess (star, infinity, sea). The man, bleeding black blood, may represent Christ with his side pierced.

- Poetry

- 70-77

La terre est bleue comme une orange

This painting exudes the happiness and calm that Montlaur found in Rothéneuf. One can see a bowed head, is it that of the beloved? The sky of Brittany is blue like Gala’s eyes.

The earth is blue like an orange

Never an error, words do not lie

They do not give you cause to sing

Turning these kisses to get along

The crazy ones and the lovers

Her, her mouth of alliance

All the secrets, all the smiles

And what clothing of indulgence

To believe her naked

The wasps bloom green

The dawn passes around the neck

Wings cover the leaves

You have all the joys of the sun

All the sun in the world

On the path of your beauty.

(Paul Eluard, Love, Poetry, 1929)

(Translated by Anna Scanlon)

- Classical literature

- 70-77

Le soleil du détroit de Messine

(The sun of the strait of Messina)

The painter must have had in mind the tragic choice of Ulysses who sacrificed part of his crew by preferring to pass near Scylla rather than Charybdis. The painting represents the hero, standing on his ship, with huge waves and a red and gold sun. The black heads of Scylla tear off and devour the bodies of his companions.

- -

- 70-77

L’étoile se lève claire sur un matin sale

(The star rises bright on a dirty morning)

The colors are not as strong as usual, they are almost pastel; they are applied in successive layers which are partially scraped with a palette knife revealing extraordinary overlays. The overall form is very constructed. We can see a star explode in the middle of the painting and flood it with its radiance. We can clearly feel the evolution of the painter’s technique during the last ten years of his life.

- Poetry

- 70-77

La licorne et le capricorne

(The Unicorn and the Capricorn)

May satyrs and Pyraustus,

and flitting fires of Aegipans,

make destinies as damned as Faustus.

That neck in noose on Calais sands —

what holocaust of pain it cost us.

Grief that doubles future mourning

of unicorn, of capricorn:

the doubtful flesh the soul is warning.

Flee the god’s flamed pyre in scorn

as stars the flowers in the morning.

(Guillaume Apollinaire, La Chanson du mal-aimé,

The Milky Way -Translated by C. John Holcombe)

The Unicorn and the Capricorn was painted in 1974, three years before Montlaur’s death. It is one of his most completed paintings. The technique he has acquired allows him to express on the canvas what he could not say in words. He writes: “[Painting] appeared to me as the way to say those important things that we could not talk about.” He adds: “I do not understand [that people] cannot guess all the distress which is there, before their eyes, as it was during the war: clamor, death, love, betrayal, lie and fear. And much more that I cannot say, but this is what I know how to do. I repeat: I know how to do.” (Petits Écrits de Nuit)

Apollinaire had already explained that Picasso’s painting was “an admirable language that no literature can explain, for our words are made in advance. Alas!” (Journal intime)

In his poem, Apollinaire reproaches his grief for “doubling future mourning”, that is to say for scaring away his soul – the unicorn – from his body – the capricorn. Grief is love, a divine pyre that lasts all night (from stars to flowers).

We can find these symbols in the painting: the capricorn is a green silhouette, seen in profile at the top and to the left of the painting. The unicorn is smaller, it is shaped like a heart, red, blue and white to the right of the center of the painting. The pyre-grief is the bright yellow and red spot of light in the upper right quadrant. We can guess a shape (a black horse?) and creatures that are difficult to identify at the bottom of the painting.

- French literature

- 60-69, 70-77

La nuit d’Aurélia

(Aurelia’s night)

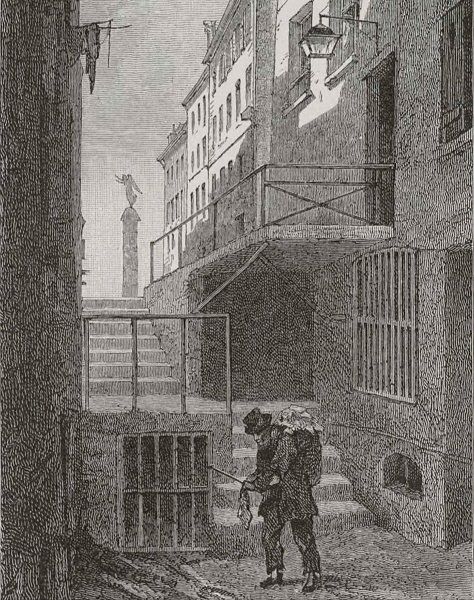

Gérard de Nerval was one of Montlaur’s favorite poets. Several paintings refer to his tragic death: “La nuit du 25 janvier 1855 rue de la vieille Lanterne” (The night of January 25th 1855, Rue de la Vieille Lanterne) and “La mort du poète” (The Death of the Poet), and to his works written just before he committed suicide: “Je suis l’inconsolé” ( I am the Inconsable), “Les filles du feu” (The Daughters of Fire) and “ La nuit d’Aurélia” (Aurelia’s Night ).

Nerval’s prose poem “Aurélia ou le rêve et la vie” (Aurelia or the Dream and Life) narrates his dreams-hallucinations, and his love for Aurélia, now dead, whom he can only meet in the underworld. He speaks of his own madness which, according to Albert Béguin, “is a poetic act par excellence” (L’âme romantique et le rêve, José Corti, 1939, p.358). Nerval mentions that he also translates his dream memories by tracing colored drawings - “series of frescoes” - which he hangs on the wall of his hospital room. For him, the borderline between dream (delirium) and reality (lucidity) is always blurred, uncertain. Montlaur could not help but be touched by the poet’s descriptions.

Abstraction allows the painter-reader to convey his perception of “Aurélia” to the viewer of the painting “The Night of Aurelia”. Here, he perfectly masters the art of reproducing the blurring of shapes and colors. Hallucination-madness invades the whole painting, we perceive human forms in the foreground “The outlines of their figures varied like the flame of a lamp, and at all times something from one passed into the other; the smile, the voice, the color of the hair, the size, the familiar gestures, were exchanged as if they had lived the same life, and each was thus a composite of all” (Aurélia). In the background, a giant star - is this metamorphosed Aurelia? with protective arms. A dark night sky.

- Philosophy - war

- 60-69, 70-77

Gnose

Gnosis γνῶσις, (knowledge). According to this philosophical approach, the salvation of the soul is only possible through the knowledge of divinity, and thereby, through the knowledge of oneself. Montlaur certainly had in mind Erik Satie’s “Gnossiennes” that he sometimes listened to while painting. He greatly appreciated the work of Satie, Apollinaire’s friend. “Gnosis” - the painting - was started in 1960 and completed in 1974. We can easily recognize the very dynamic gesture of Montlaur’s 1960s period, and his 1970s “finish” brings a chromatic richness that we find in all of his later paintings. For Montlaur, ironically, knowledge of his deepest self was only made possible by the wound he suffered in his skull; gnosis had thus become an autopsy. We can see the white outline of his head and neck and the shrapnel fragment, square and black, which entered Montlaur’s right cheek on the morning of November 1, 1944, when he landed with the Commandos in Flushing, Holland. He suffered from that wound his entire life due to fragments of metal having penetrated his sinuses and his eyes.

Listen to the “ Gnossiennes ”

- Religion

- 70-77

Peinture ambigüe et figurative de Saint Christophe - ou - There are Things that it would be far Better not to Know

The painting has two titles: “Peinture ambigüe et figurative de Saint Christophe” (Ambiguous and figurative painting of Saint Christopher) and “There are things that it would be far better not to know”

In the background, one can clearly see the river the saint is crossing and the cross he carries. Surprisingly, his head resembles that of the artist; did he really represent himself in the painting?

And why the cryptic phrase “There are things that it would be far better not to know”? What is the artist referring to? Past memories? Things that are unspeakable but representable on the canvas provided they are ambiguous and abstract.

- -

- 70-77

La mort dans l’âme

(With a Heavy Heart)

There is so much grief in this painting with such an explicit title! The work leaves room for the imagination of the observer, it imposes it. Is this the painter we see standing, his shoulders down? The blue of his back and arms contrasts with the black of the terrifying creatures surrounding him. Contrast also with the red ocher roofs of the city and with the mountains behind with unreal colors.

- War

- 70-77

Facies personae

“Facies personae” can be translated as “silhouette of a person” or “mask of a character”. We have very few elements that would help us decipher this painting properly. A resistant friend of the artist, Jacqueline Péry d’Alincourt, who had been deported to the Ravensbrück concentration camp (from April 1944 to April 1945) and had survived, told him that she could find in this painting fragments of her memories of the camp: silhouettes of deportees, the smoking chimney of the crematorium ovens at the top of the painting. We can see of course, a lifeless mask occupying the entire center of the painting. Note the black background of the scene and yellow sky blackened by the ovens’ smoke.

- War - music

- 70-77

Es war ein wunderlicher krieg

The title given by Montlaur to this painting is the first verse of the 5th stanza of Johann Sebastian Bach’s cantata BWV n ° 4 “Christ Lag in Todesbanden” (Christ Lay in Death’s Bonds). The musician celebrates the victory of life over death in a strange war. Bach took up a text written by Martin Luther in 1524.

The painter-soldier, inspired by Bach’s musical work, reproduces a war scene on the canvas: his war. He paints the hand-to-hand combat between the forces of good – the blue forms - and those of evil - the black black forms - in the midst of vermilion flames.

Es war ein wunderlicher Krieg,

Da Tod und Leben rungen,

Das Leben behielt den Sieg,

Es hat den Tod verschlungen.

Die Schrift hat verkündigt das,

Wie ein Tod den andern fraß,

Ein Spott aus dem Tod ist worden.

Halleluja!

It was a wondrous battle,

Where death and life wrestled;

Life got the victory;

It has swallowed up death.

Scripture has proclaimed this:

How one death devoured the other,

A mockery was made of death.

Hallelujah!

(translation by Michael Marissen and Daniel R. Melamed)

Listen to: Es war ein wunderlicher Krieg

- War

- 70-77

One June Early Morning

The painting evokes the landing of Sergeant de Montlaur on the morning of June 6, 1944. Its construction is very neat, almost geometric. The painter uses the diagonals to represent the large anti-tank and anti-barge metal crossed beams that stood on the beaches. The painting is dynamic: one can imagine the soldier running up the beach, enemy bullets hitting the sand around him. A white swirl symbolizes movement, perhaps the fall of a body or the blast of a shell. As in the painting “Souvenir Normand” , which was painted in the same period of time, the bright colors symbolize blood -red, fire -yellow, metal -black.

- War

- 70-77

Souvenir normand

(Memory from Normandy)

The painter remembers 28 years later, the day of June 6, 1944 when he landed on the French beaches, in Colleville-sur-Orne (now Colleville-Montgomery). He sees flashes, explosions, shards of black metal and blood. The sea is below, the sky above. The painting is very dynamic as if the painter had reproduced the movements as well as the colors.

- Music

- 70-77

Actus Tragicus

Montlaur always painted while listening to music, mostly by Johann Sebastian Bach. The title of this painting is that of Cantata BWV 106 “Gottes Zeit ist die Allerbeste Zeit” (God’s time is the best of times), a short work composed when Bach was about 23 years old. The theme is that of death which happens at a time chosen by God. The flutes are particularly moving. The voices are consoling but remain very sad.

Is it the dead we can perceive - the black shadow of a head behind a curtain of gray and white tears that flow profusely? There is a light in the center of the painting: a glimmer of hope and confidence that death is opening the way to paradise, and therefore to happiness.

Listen to Actus Tragicus

- Medicine - war

- 70-77

Pseudo-métabolisme

(Pseudo-Metabolism)

Does the painter feel affected by a disease he cannot control? We can see in the center of the painting a black shape encompassing and crushing a scarlet heart. Can we interpret this as war memories (information or “material” according to the theory of Fritz Perls, founder of Gestalt Therapy), which cannot be assimilated (“metabolized”) and are projected in the form of aggression? I imagine that Montlaur was able to discuss this theory with his friend Professor André-Dominique Nenna, a doctor and art collector, a great lover of paintings, Montlaur’s in particular.

- Poetry

- 70-77

Automne

(Autumn)

A bow-legged peasant and his ox receding

Through the mist slowly through the mists of autumn

Which hides the shabby and sordid villages

And out there as he goes the peasant is singing

A song of love and infidelity

About a ring and a heart which someone is breaking

Oh the autumn the autumn has been the death of summer

In the mist there are two gray shapes receding

(Guillaume Apollinaire, Alcools, Autumn, translated by W. H. Merwin)

The poet describes a sad misty autumn landscape, with a bow-legged peasant following his ox and weeping for a lost love.

The painter probably refers to his own autumn. The landscape is dark, the ground is earthy, littered with brown and red leaves. The peasant at the bottom of the painting has his arms outstretched (one blue, one red), he is behind his black-rumped ox. One can see in the distance the black hamlets against a filthy green and grey sky with a large blood-red sun.

- Poetry - war

- 60-69

Il dort

(He is Sleeping)

This is a tribute of the painter-soldier to an anonymous 45th Royal Marines Commando, who was killed in the days following June 6th, 1944, in Normandy. In this very harsh painting, Montlaur does not only refer to Arthur Rimbaud’s poem “Le dormeur du Val”, he follows to the letter the poet’s description, including colors.

Le dormeur du val (The Sleeper in the Valley)

It’s a green hollow, where a river is singing

Crazily hanging on the grasses rags

Of silver; where the sun, from the proud mountain,

Is shining: it’s a little valley bubbling with sunlight.

A young soldier, his mouth open, his head bare,

And the nape of his neck bathing in cool blue watercress,

Is sleeping; he is stretched out on the grass, under the skies,

Pale in his green bed where the light falls like rain.

Feet in the gladiolas, he is sleeping. Smiling like

A sick child would smile, he takes a nap:

Nature, rock him warmly: he is cold.

Fragrances do not make his nostrils quiver;

He sleeps in the sun, hand on the breast,

Peacefully. He has two red holes in his right side.

(Arthur Rimbaud, Le dormeur du val , translation by Camille Chevalier-Karfis, June 21, 2021)

- Death - war

- 60-69

Sur la route, vers Sallenelles, un ami

(On the Road near Sallenelles, a Friend)

In the days following the D-Day landings, Sergeant de Montlaur and his comrades of the Free-French No. 4 Commando 1st BFMC (Battaillon de Fusiliers Marins Commandos also called “Kieffer Commando”) took part in intense and violent fighting against the German troops stationed near the village of Sallenelles and the Bavent Woods on the North bank of the Orne River in Normandy.

The painter could not be more realistic: the impact of a bullet or shrapnel in the forehead, the blood that flowed from the mortal wound, the greenish and blue tint of the face of “his friend” are reproduced in this painting in all their horror. Why “a friend”? The man has a green commando beret. He is certainly one of Montlaur’s commando comrades. Probably one of those who were killed on June 10 or 11 near Amfreville.

- Landscape

- 60-69

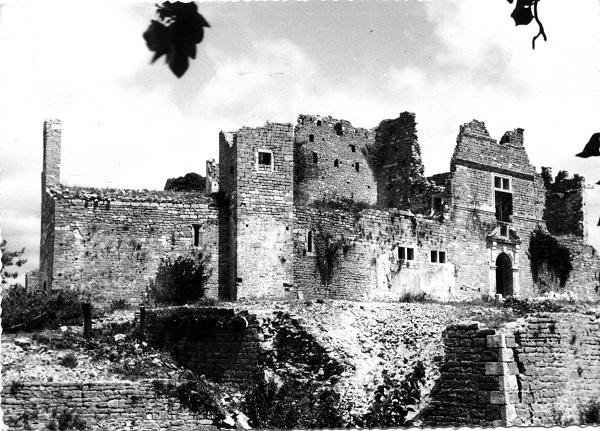

Lonesome October

The Chateau de Montlaur as seen by Montlaur in 1968. The painter represented the Renaissance façade of the castle with the chapel and its red roof and the majestic entrance surmounted by a cross-window.

The Chateau de Montlaur (11th century) is the cradle of the Montlaur family. It is located 18km North-East of Montpellier. This Catholic stronghold was besieged by the Protestant troops of Henri, Duke of Rohan and taken on Easter Monday, March 28, 1622. The fortifications were cannonaded and razed, the castle was plundered and burned, the garrison massacred – according to Catholic sources, the bodies were eaten by dogs and left to rot. The lord, François de Montlaur-Bousquet was imprisoned in Sommières and released on bail. Reconstruction of the chapel and of the main façade was started around 1630 but quickly stopped due to the opposition of King Louis XIV’s prime minister, Cardinal Richelieu.

- German literature - war

- 60-69

Je vous demande pardon, ma Mère Courage

(I Ask for your Forgiveness, my Mother Courage)

It is a vision of storm and calamity. The ground is black, marked by fire. The mother, a dark shape, is holding in her arms her dead daughter -a white form with red hair.

The painter identifies with the murderous soldiers and asks the mother to forgive him.

- French literature

- 60-69

L'abbaye de Thélème

(The Abbey of Theleme)

“The architecture was in a figure hexagonal, and in such a fashion that in every one of the six corners there was built a great round tower of threescore foot in diameter, and were all of a like form and bigness. Upon the north side ran along the river of Loire, on the bank whereof was situated the tower called Arctic.”

(François Rabelais, Gargantua and Pantagruel, Book I, Chapter LIII)

(Translated by Sir Thomas Urquhart of Cromarty and Peter Antony Motteux)

The abbey occupies the center of the painting. Its shape is triangular rather than hexagonal. One can clearly see the round towers as well as the Loire river. The painting is balanced and reflects the joie de vivre of the monks of the Abbey.

- Philosophy

- 60-69

Hypostase d’un peintre singulier … et peut-être universel

(Hypostasis of a Singular … and Perhaps Universal Painter)

Hypostasis: (ὑπόστασις) action of placing oneself (στάσις) below (ὑπό-) = foundation, first substance.

The artist is hermetic, as is often the case; is he talking about his soul engendered - or not - by his intellect? Does he believe he can achieve (universal) beauty through abstraction? Yet, his painting remains hermetic: in the foreground, we can see a humble silhouette with red hair, the author; and above it, another form, threatening and violent, all of fire and light under a dark sky.

- -

- 60-69

Souvenez-vous

(Remember)

This painting is peaceful and strong. We can see a sphinx, majestic, powerful, and patient. He is surrounded with light and fire.

What and whom should we remember? What is the sphinx looking at? Is he protecting us?

- Death - War

- 60-69

Du sang sur la route

(Blood on the Road)

A tragic event will will affect the artist deeply and for a long time. In August 1966, Montlaur was on vacation in Brittany. The car in which he was a passenger collided with a young boy on a moped. He helped him and stayed with him for a long time, speaking to him, trying to reassure him while the child was dying.

The horror of the painting does not need to be described.

- Landscape

- 60-69

On commence à comprendre - ou - On n'a jamais rien compris

The painting has two titles: “On commence à comprendre” (We are Starting to Understand) and “On n’a jamais rien compris” (We have Never Understood Anything).

Shapes are no longer geometrically arranged as they were in older paintings. We thought we understood, now everything is blurred but the harmony is intact, the colors are strong and contrasting. We are in Brittany, the sea is rough, blue and green, the rocks are sinister.

- Painting

- 60-69

Hommage à Gustave Courbet

(A Tribute to Gustave Courbet)

How could one not see Courbet’s “The Origin of the World” in this painting?

Montlaur had great admiration for the work of Gustave Courbet and for Courbet himself, in particular his participation in the Paris Commune (from March 18 to May 28, 1871). It should be remembered that Courbet was an elected representative of the Commune and was elected President of the Federation of Artists. He prevented the Louvre collections from being looted and damaged.

- Painting - classical literature

- 60-69

La chute d'Icare

(The Fall of Icarus)

Montlaur used the same title as Brueghel the Elder. The original work, painted around 1558, has disappeared. Two copies are known, one of which (below) was dated 1583; it is exhibited at the Van Buuren Museum in Brussels.

If we take a close look at Brueghel’s painting, we can see, between the ship and the angler, the legs of the unfortunate Icarus drowning (detail in the image below).

Montlaur’s painting is far more violent than Brueghel’s. The neo-aeronaut’s legs are clearly visible in the midst of tumultuous blue and green waves: they are the black shapes in the lower half of the painting.

- -

- 60-69

Sans titre

Montlaur’s style has evolved: it is more structured and planned. His painting is much less violent than before: colors are pale and shapes are polygonal. There is no more glazing effect and the top layers are scraped with a palette knife to reveal a spectacular play of colors.

- War

- 60-69

Avant le déluge

(Before the Flood)

The painter evokes the omens of the war which changed the course of his life: the carefree student-painter has become a soldier, he has discovered combat, blood, fire, death, chaos. It is this chaos that he represents in this abstract but so expressive painting. The shapes and contours are difficult to define, they seem to hide a head with flaming hair, the sky is black on one side, it is on fire on the other. We see no optimism, but just the reality of horror to come.

- Painting

- 60-69

Le jugement de Pâris

(Judgement of Paris)

Montlaur’s painting is inspired by the “Judgment of Paris” attributed to the Italian Renaissance painter Giulio Romano (1499 - 1546), a disciple of Raphael. One could even call it an an “abstractized” copy of Romano’s work. The three goddesses Aphrodite, Athena, and Hera are about to see one of them, Aphrodite, be declared by Paris the most beautiful goddess in the Olympus and receive the apple. In Montlaur’s “Judgement,” we can see Aphrodite, naked, sitting at the foot of massive and dark trees, Athena is standing, and the volutes of Hera’s scarf are obvious. The background is also reproduced: the sky and the distant landscape are similarly blue and green, the earth is ocher.

- Religion

- 60-69

Mater Dei

(Mother of God)

The portrait is peaceful, gentle, full of kindness and sorrow. The color blue predominates in the background. White plays a fundamental role: it softens the scene and together with black provides volume to the picture. Red is rare - only the Virgin’s lips, surprisingly.

Montlaur writes: “I understood that for me (painting) was more ‘allusive’ than any other mode of expression. Music and the verb (spoken or written) are obviously equally so for others. The difference with painting is that it concerns me directly. I had the revelation that I could express the mystery, my mystery, through painting, my painting” (Petits écrits de nuit, 1961).

- Classical Literature

- 60-69

L'ombre d'Anchise

(The Shadow of Anchises)

Aeneas accompanied by the Cumaean Sibyl descends to the world of the dead in order to bring back his father Anchises. The latter introduces him to his descendants: Romulus and Remus, Pompey, Caesar and Augustus. He refuses to go back to the world of the living. (Aeneid, book VI).

- Portrait

- 60-69

Portrait par lui-même d'un peintre aveugle

(Self-Portrait of a Blind Painter)

Montlaur, all in self-deprecation, continues to experiment with his color technique. He uses the glazing process on all his future works. The black background of his nights and his memories remain omnipresent.

- Poetry

- 60-69

La promesse des fleurs

The artist uses Malherbe’s words in his “Prayer for King Henry the Great” in which the poet celebrates peace finally brought back to France by King Henry IV. The colors remain violent, there are threatening black shapes, like painful memories that cannot be deleted.

Never again will we encounter these sad years

That, for the most fortunate brought nothing but tears.

Our families will be laden with all kinds of goods,

The harvest of our fields will become tedious for sickles,

And fruit will fulfill the promise of flowers.

The end of such great trouble we suffered

Will delight our senses with wonder and with joy;

(François de Malherbe, 1605)

(Translation by G de Montlaur)

- Death - war

- 60-69

Souvenir d'un meurtre

(Recollection of a Murder)

What murder is this? We do not know. One can see the obvious burial cross, brown earth, mud, green decaying matter, red blood. The artist describes the horror of a memory, certainly in wartime.

- Poetry

- 60-69

L'espoir a fui

The artist quotes Verlaine who, in his “Colloque sentimental”, recalls his past love.

In the painting, shapes are cold and bloody, they pierce the black sky.

In the old park’s desolation and frost

the paths of two ghostly figures have crossed.

Their eyes are dead and their lips slack and gray

and one can scarcely hear the words they say.

In the old park’s desolation and frost

two spectres have been evoking the past.

- “Do you recall our bliss of that September?”

- “Why ever should you wish me to remember?”

- “Now when you hear my name does your heart-rate grow?

Do you still see me in your dreams?” - “No.”

- Ah, the enchantment of loving so dearly,

those kisses that we shared!” - “Did we really?”

Skies were so blue and hopes so high, so proud!

Defeated hope has fled in a sombre cloud.

Thus did they walk in the wild grass swaying.

Only the night heard the words they were saying.

(Paul Verlaine, Colloque sentimental)

(Translation : Peter Low)

- Poetry

- 60-69

On a brûlé les ruches blanches

(The white beehives have been burnt)

Ever since he started painting, Montlaur found his inspiration in the works of Guillaume Apollinaire, the poet closest to him figuratively but also physically. Montlaur kept Apollinaire’s “Alcools” with him throughout the war, and in particular when he landed on the Normandy beaches on D-Day.

And you crawling after me

God of my gods who die in autumn

Who measure out what life

I have a right to

My shadow my ancient serpent

Since you adore it I led you

To the sun remember

Shadow wife I love

Because you are nothing you are mine

O my shadow mourning me

Winter is dead covered in snow

The white beehives have been burnt

In gardens and orchards

Birds on branches sing

Bright April airy Spring

(Guillaume Apollinaire, La Chanson du Mal-Aimé,

The Milky Way -Translated by Martin Sorell)

As in his paintings Sainte-Fabeau and La licorne et le capricorne , Montlaur reproduces on the canvas verses from Apollinaire’s La Chanson du Mal-Aimé. The poet asks his shadow, “his dark wife”, how many spans of earth he will need to dig his grave. Now winter is dead, the beehives have frozen and are burning, the birds are singing, it is springtime.

One can easily recognize the white beehive, with yellow and red flames, a blue sky. There are a few spans of earth at the bottom of the painting.

- Religion

- 60-69

Stabat Mater

Images overlap: the face of the Virgin Mary submerged with by pain, and her head filled with the passion of Christ on the Cross. Did the painter represent the Mother or the Son? Who is who? Listening to Pergolesi’s Stabat Mater (link below) will help the viewer see what the painter is telling us – Montlaur listened to the Stabat Mater all the while he was working on this painting. The emotion from the music is the same as that from the painting that literally pierces the canvas, but remains abstract if it cannot be “seen”, by the viewer. The mystery remains deep.

This painting can be seen at the Passionist Fathers’ Saint Joseph’s Church, 50 Avenue Hoche in Paris.

Listen to the Stabat Mater on: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xHQVtYzjLao&ab_channel=TerryTirlipirli (Pergolesi - Stabat mater, Margaret Marshall, Lucia Valentini Terrani, London Symphony Orchestra - Deutsche Grammophon )

- War

- 56-59

Ciel strié d'oiseaux

(Sky Streaked with Birds)

Expressionist period.

The birds are like Stukas, black and threatening. They have invaded the sky which explodes with blinding colors. Nightmares never leave the painter’s nights.

- Landscape

- 54-55

La gloire du matin

(Morning Glory)

“Fontainebleau” style period.

17 years later, the painter recalls the Forbach blast furnaces he saw in 1938 while doing his military service with the “18e de Chasseurs” (cavalry hunter batallion) at Saint-Avold in 1938.

- Poetry

- 54-55

Sainte-Fabeau

(Saint-Faggot)

This painting is representative of the period when Montlaur lived in Fontainebleau. This characteristic style follows his abstract-geometric period of the early 50’s where shapes and colors were well defined and perfectly delimited. Here, in a first stage, the painter “covers the canvas” (in his own words), then, he substitutes the palette knife for the paintbrush. He breaks the shapes, scrapes the thick layers of paint to reveal the underlying color(s). The resulting shapes become ghostly, fantastic creatures, dark inhabitants of his never-ending nightmares, his war memories.

The title of the painting comes from Guillaume Apollinaire’s poem “Les Sept épées” (The Seven Swords). Sainte-Fabeau (Saint-Faggot) is the fifth of these swords.

Fifth, the Saint-Faggot is bright

and is the fairest of distaffs.

A cypress on a tomb, alight

where four winds kneel and force their draughts

in torches’ flaming, night on night.

(Guillaume Apollinaire, La Chanson du mal-aimé,

The Seven Swords -Translated by C. John Holcombe)

This stanza is about death: the distaff in the hands of the Fate, the cypress, the tomb. The sword is one that pierced the heart of the Virgin Mary and maybe also one of the seven deadly sins. As always, Apollinaire plays on the meaning of words, in the same way, the painter plays on the colors and the shapes of his creations.

One can see, lying at the bottom of the painting a gray shape with a red cross, is this the tomb? White forms fall from the sky, others, black and blue are kneeling. Montlaur was perfectly acquainted with the poems of “Alcools”, it is certain that he wanted to faithfully reproduce in his painting the hermetic words of the poet.

- French Literature

- 54-55

Divertissement pour la nuit de Janvier

(Entertainment for the Night of January)

Montlaur once again refers to the tragic end of Nerval, his suicide on the night of January 25 to 26, 1855, Rue de la Vieille Lanterne in Paris. It was only a few days after the publication of the first part of his book Aurélia where he described his premonitory dreams.

This is the crux of the artist’s “Fontainebleau” period: he uses almost exclusively a palette knife and plays with the superimpositions of layers of different colors by scraping them. The brightly colored shapes seem trapped in an ink-black world.

- French literature

- 54-55

Le rêve de Nerval

(Nerval’s Dream)

Montlaur refers to the hallucinatory dreams described by Gérard de Nerval in Aurélia. The publication of these dreams - where real and imagined life are hardly distinguishable - preceded the poet’s suicide by a very short time.

The artist finally frees himself from form and geometry. He trades the brush for the palette knife, he destroys the outlines. His imagination can now express without hindrance his dreams, too often nightmares, and reality.

- Painting

- 50-54

Le maître de Moulins

(The Master of Moulins)

Montlaur pursues his search for perfection. He associates shapes and colors following the principles of his friend, the painter Gino Severini: “the colors are determined in an almost mathematical way and follow rigorously from the forms” (Du cubisme au classisisme, 1921). Here, the artist was inspired by the triptych of the cathedral of Moulins where Virgin and Child are framed in a mandorla, with a nebulous sun shining in the blue of the sky.

- -

- 50-54

Paysage n° 2

(Landscape n° 2)

In 1950 Montlaur has abandoned the cubism of his American years. His painting is abstract and one can sense the influence of his friend and mentor Gino Severini. The shapes are dynamic and the colors bright, like the green of this landscape.

- Portrait

- 46-49

Portrait d'Adelaide de Montlaur

Cubist portrait of Adelaide, comtesse de Montlaur .

Adelaide Piper Oates was born in Brooklyn, NY. She went to France in 1937 to learn French and Fine Arts and met Guy de Montlaur in Paris. At the start of the war, she had to return to the United States. In order to join Guy de Montlaur, Adelaide obtained from the US State Department to be sent to England at war. She arrived there in June 1943 and married Guy in Denham, Buckinghamshire (UK). Guy was then part of the Free-French N° 4 Commandos, commanded by Cdr Philippe Kieffer and Col Robert Dawson. She remained in England until the end of the war, while her husband was fighting in France and in Holland.

We will not forget her great strength of character and her courage.

- Poetry

- 46-49

Alcools

(Alcohols)

This painting is dedicated to “Alcools,” Guillaume Apollinaire’s collection of poems. The book was with Montlaur throughout the war and even took on water on the beach of Colleville-Montgomery (at the time Colleville-sur-Orne) on the early morning of June 6, 1944.

Montlaur very often refers to Apollinaire, his favorite poet, as evidenced by the titles of his paintings: Ma Désirade, The Unicorn and the Capricorn, Autumn, We Burned the White Hives. Apollinaire had been a poet and a soldier just as Montlaur, one World War later, was a painter and a soldier. Both were injured in the head and suffered from their injuries. Alcools was one of the first paintings Montlaur exhibited: in March 1949 at the Galerie Lucienne-Léonce Rosenberg, in Paris.